By Neera Kuckreja Sohoni

Eleven years after Gandhi’s death, Martin Luther King on his visit to India asked for permission to stay in the modest bedroom where Gandhi used to sleep. While sleeping in that austere setting he said he felt vibrations of the Great Soul. Later in an interview, King told All India Radio that he had decided to adopt Gandhi’s method of civil disobedience as his own.

Today’s Woke generation and academia would scoff at King’s insistence on seeking to transcendentally connect with one whom they despise for his racially disparaging comments about Blacks.

Reverence for Gandhi is not what it used to be and not as much among students and scholars, who caricaturize Gandhi by referring to him as a sexual freak who slept nude with young girls, including his niece.

Woke scholars and stakeholders committed to dissing long-cherished American icons such as George Washington, Jefferson, and Lincoln, can hardly have spared Gandhi. For them, King’ reverence for Gandhi is as misplaced as would be their own reverence towards King.

Following the brutal killing in 2020 of a black man by a savage white cop that shook the conscience of a nation, Americans rose as one to acknowledge the shame of racism that had persisted since the birth of America, blemishing its democracy.

Howsoever just and understandable, the BLM (Black Lives Matter) protests against memorializing icons who were slave-owners may have had merit if they had chosen non-violence. Instead, by defiling and toppling iconic sites and statues, including one of Gandhi, they fell way short of what a more principled Gandhi and King would have advised or elected to do.

It is so much easier to take to the streets and burn down shops and police stations to express your rage against the racial oppression to Blacks as happened in American cities and neighborhoods, than to stand unafraid and suffer the blows inflicted on you and other protesters and not flinch, as hundreds of Indians did during the famous Salt March in India in 1930, or what King’s brave warriors did in Selma, Alabama in 1965.

Likewise, it is easy to ‘take a knee’ as a fearless act of irreverence to your nation’s anthem as Colin Kaepernick did within the insulated safety of a football arena than to face the oppressor’s barrage of bullets while celebrating a festival in a park with no exit left to escape as happened in India’s Jallianwala Bagh.

Gandhi’s methods of protest offer a study in contrast.

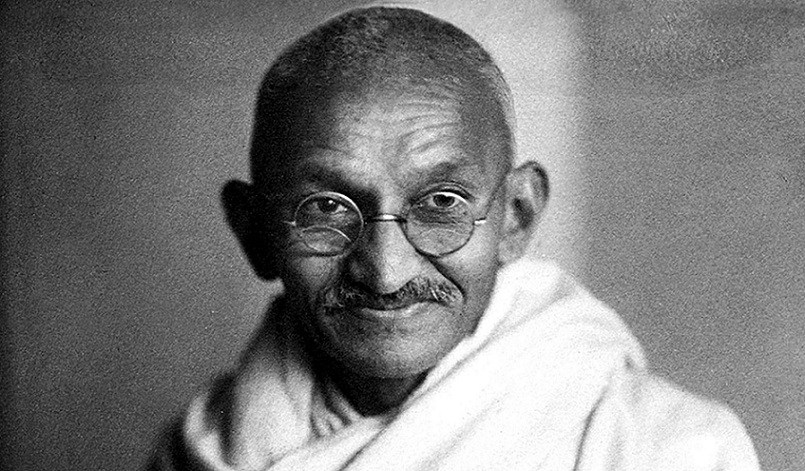

Born on October 2, 1869 in India, Gandhi went to England at age 18 where he studied law, becoming possibly ready to return to India to live the ‘civilized’ life of an England-returned Indian professional. But his karma put him on an entirely different trajectory.

Hired to render legal assistance to the Indian trading community in South Africa, he arrived in Durban in April 1893 where the racial segregation and discrimination experienced by Indian immigrants shocked him. At his maiden appearance in a Durban courtroom, when ordered to remove his turban, Gandhi took the high road. He refused to do so and left the court, only to be slighted by the local media as “an unwelcome visitor.”

A cathartic moment came on June 7 when, despite having a duly purchased first-class ticket, but because a white man objected to his presence, he was asked to leave the compartment and move to the rear of the train. His refusal to do so caused his forcible removal from the train.

That single act of unfairness and his utter humiliation evoked the warrior in Gandhi. He resolved to devote himself to fighting that “terrible disease of color prejudice” and to commit himself “to suffer whatever hardships came his way”.

The unfairness he had been shown made him a life-long advocate of fairness for all.

The following year in 1894, Gandhi founded the Natal Indian Congress to fight discrimination. His battle for gaining civil rights had begun.

After returning briefly to India to gather his family, he resumed his mission in South Africa.

Using his spare time to study leading thinkers including Thoreau – an American and Tolstoy – a Russian, and scouring Marxist, Hindu, Christian, and other religious texts, he honed his thinking. Thoreau’s 1849 essay on Civil Disobedience must have come to Gandhi like manna from heaven.

Mentally ready, Gandhi organized his first mass civil disobedience campaign in 1906, to protest the South African Transvaal government’s restrictions on the rights of Indians, including its refusal to recognize Hindu marriages and its imposition of a new tax. He termed the protest “Satyagraha” meaning ‘the Force of Truth’.

The government retaliated by hounding and imprisoning hundreds of Indians, including Gandhi. Eventually, under pressure and as news of peaceful protest caught the attention of global media, the government caved in, ceding the two demands put forth by Indians.

The first chapter of the efficacy of peaceful protest was written and the success of that novel modality was acknowledged. It was time to go back home.

His arrival in India in 1915 coincided with a global conflagration – World War I – which challenged both the colonial regime and Indians seeking to evict it.

Gandhi’s reputation as an organizer of the people’s movement preceded him. Working closely with leaders and workers of the Indian National Congress, Muslim League, and others, Gandhi guided the struggle for achieving home rule. By 1920, he had become the voice of the nation as well as the custodian of its conscience.

His means to fight the British were simple. No weapons. Instead, a strong will to stand up to injustice was what he required of the people. Indians had to renounce their submissiveness, which was keeping the British in command of India. But in all cases, they had to vow to remain non-violent.

“Nonviolence”, wrote Gandhi in 1920, “does not mean meek submission to the will of the evil-doer, but it means the pitting of one’s whole soul against the will of the tyrant…. And so I am not pleading for India to practice non-violence because she is weak. I want her to practice nonviolence being conscious of her strength and power.”

Between 1920 and 1942, under his stewardship, major nationwide campaigns of nonviolent resistance were undertaken. Included in these mass movements was the historic march to the sea in 1930 to collect salt to protest the government monopoly on its manufacture and its imposition of a salt tax, and in 1942 the powerful “Do or Die” Quit India movement.

Any departure from non-violence – whether communal or racial – caused him to call off the protest and to offer his own life in exchange for ending the carnage. In a cruel irony, his message of peace lay shattered in the violence that coincided with independence. The Hindu-Muslim slaughters accompanying India’s partition into two free nations left him a broken man. But he continued the peace-seeking effort right till his end on Jan 30th 1948 when he fell to an assassin’s bullet.

His death was not in vain. It helped restore sanity to the people and put the newly formed nations on the path to healing.

Alas, people – both Indians and Pakistanis – have long set aside Gandhi’s core principle of amity. The uniquely peaceful approach to battling injustice that Gandhi propagated was pivoted not only on civil disobedience but also on civility. Hence his advice to remain courteous to all including to the enemy –

“We must love the British and through our peaceful strength and love, we will change them. We must demonstrate to every Englishman that he is as safe in the remotest corner of India as he professes to feel behind the machine gun”.