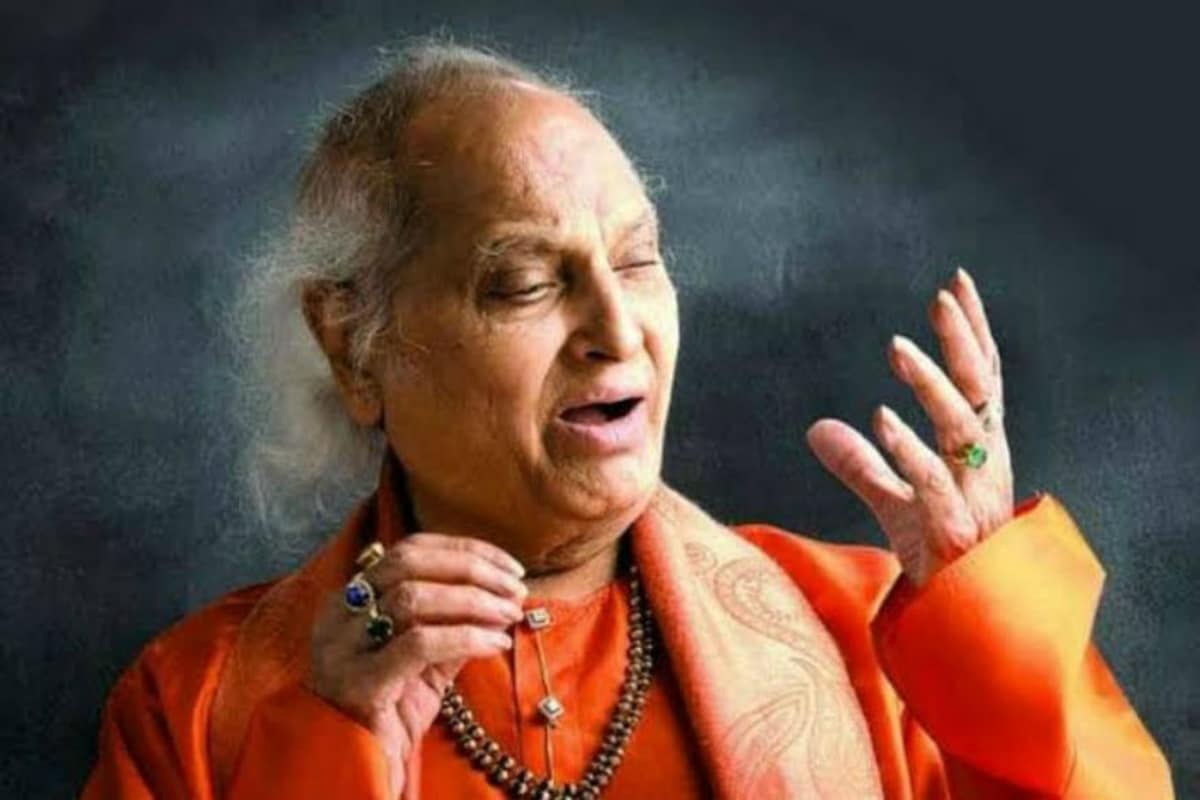

Hindustani classical vocalist Pandit Jasraj had once said, “I believe music is not something you can perfect even in a lifetime. With every life, you start off from where you left off in your previous life. Once you have understood this, age is no more a barrier and death is not the end of your musical pilgrimage.”

If this is true, today is a mere punctuation in the maestro’s pilgrimage towards music, as we collectively mourn his death. India’s culture-scape is left with a void that cannot be filled.

For the last eight decades, his mellifluous and powerful voice gave the audiences the rarest of the gift, and lured Gods to earth. Surely, anyone who has ever heard his performances would attest that they felt the presence of the divine and were surrounded by spirituality that is perhaps not found in any other musician’s works.

The maestro’s journey towards that spirituality through music started early in life. In 1944, the sole bread earner of their family, his elder brother Pandit Maniram, lost his voice and was unable to sing. At the time, Maharaja Jaywant Singh of Sanad took the responsibility of the family. The Maharaja was also instrumental in helping Pandit Jasraj’s elder brother get his voice back as he insisted that Maniram sing devotional songs at his Kali temple.

When Maniram, accompanied by a young Jasraj, stood at the temple, he felt the goddess herself was guiding him to sing, and suddenly found his voice back and could sing again. He was so happy and amazed by that discovery that he sang through the night and his singing career obviously got a new lease of life after that. This incident left a deep impact in Pandit Jasraj’s heart, and he veered towards devotional music from then on.

Music to him was always a means to communicate with God, and he found many different ways to communicate. Originally from the Mewati Gharana, the maestro had composed over 300 hundred bandishes during his long illustrious career. He was also a trailblazer in singing ancient Sanskrit verses of great saint-poets in Indian classical style, which gave birth to a spiritual revolution in classical music. He not only sang Meera bhajans but also Vedic chants. His vocal range was matched only by the range of music he sang and composed.

One of his most unique characteristics was that he could sing over all four and a half octaves, even at a very old age, the credit of which he always attributed to his ‘aradhana‘ (devotion) and God’s blessings. His voice always blended sensitivity, an emotional approach to chaste classical techniques, which often gave his songs a unique lyrical quality that reaches out to people’s hearts.

He also embraced Khayal and ‘influenced the romanticist movement that swept Khayal vocalism since 1970s’. There are many lores about the miraculous powers his voice possessed, and some even say his rendition of Raag Malhar could make it rain.

Over the years, the musician researched on Haveli Sangeet and made several contributions to this genre. Haveli Sangeet is sung as hymns and is a kind of devotional music that recounts Lord Krishna’s childhood. However, his biggest contribution was the Jasrangi, a unique duet in which a female and a male singer, each with a different set of accompaniments, sing different ragas in their own scales, weaving them seamlessly into a harmonious whole. (Source: news18.com)