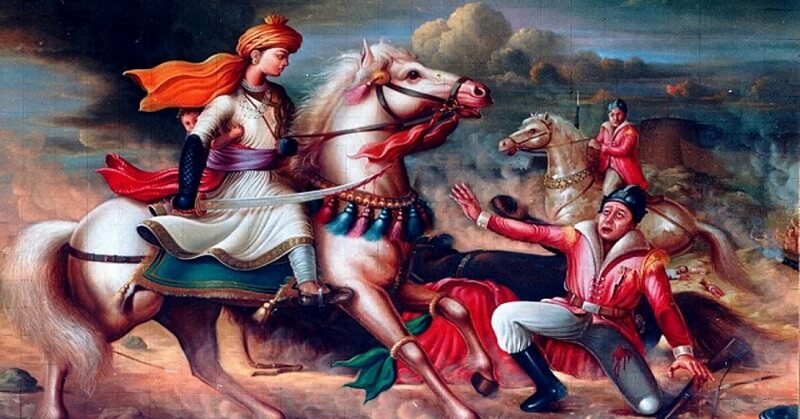

Although born centuries apart, both warrior women had a common enemy – the English

By Neera Kuckreja Sohoni

Throughout history, while women have suffered the brutality of war, sacrificed their sons, husbands, and fathers, and seen women captured, raped, forcibly converted and wedded, or slaughtered, few examples exist of women warriors and even fewer warrior queens. Among exceptions that prove the rule are two names that dominate – Lakshmibai and Joan of Arc.

Although born centuries apart, both warrior women coincidentally had a common enemy – the English.

Charged with several offences including witchcraft, heresy, and dressing like a man, Joan was burnt at the stake in 1431 as a heretic by her enemies. Although subsequently exonerated by the French King and recognized as a martyr, it was only after 500 years – in 1920 – when the Catholic Church canonized her as a saint.

Born in 1412 to a poor family of tenant farmers in Domremy, France, Joan had a humble beginning. She grew up helping her parents with the usual exacting domestic and farming chores. But a higher calling beckoned her. France and England were then engaged in a hellishly long conflict known as the Hundred Years’ War – fought around the rights of contesting claimants to the French throne.

Barely 16, young Joan experienced mystical visions that convinced her she was meant to help save France from the British. Unafraid, she sought and succeeded in getting a meeting with Charles (son and heir of the French King Charles VI) and managed to secure his approval of her solemn mission to expel the English and install him as the rightful king.

Dressed in male attire with her hair clipped, Joan successfully led the French army to victory over the English at Orléans. Much like famous generals who are eternally known as heroes of the battles they won, Joan was identified thereafter as the ‘Maid of Orléans’.

While she lived to see Charles crowned as King, in a subsequent battle to which Charles dispatched her, she was wounded and taken prisoner by the enemy who handed her over to the British in exchange for a rich ransom. Charles selfishly showed no interest to step in and save her. Eager to make an example of her, the English allowed the church to try her at the end of which she was sentenced to burn at the stake. She was not yet 20.

Lakshmibai had a more prosperous beginning. Born in 1828 in Varanasi to a Maharashtrian Brahmin family, she had a privileged childhood. Her father was a military commander who worked for Peshwa Baji Rao II. Formally named Manikarnika Tambe, she was nicknamed Manu.

Sadly, Manu was barely four years old when her mother died. But her father ensured she received excellent homeschooling. In addition to the 3 R’s, she learned martial arts, fencing, shooting, and riding. Perhaps her mother’s absence made her less susceptible to the strictly feminine norms and patriarchal expectations of female behavior. She was noticeably more free-willed and independent than girls typically were able to be then or in conventional settings even now.

Among her childhood friends were Nana Sahib and Tantia Tope, who along with Lakshmibai, were destined to later play pivotal roles in the first national challenge to British rule in India.

Reviled by the British for almost a century as a Mutiny, but celebrated now as the First War of Independence, this 1857 “uprising” shook the sleeping conscience of enslaved Indians regardless of their gender, faith, caste, or calling. It led eventually to India gaining its independence in 1947 ending British colonial rule while also sounding the death knell of colonialism everywhere.

Manu’s childhood was a predictor of her future. At age 14, married to the Maharaja of Jhansi who named her Lakshmibai, she learned to be and think like a reigning queen. Some years later, she delivered an heir who died in infancy, leading the couple to adopt a child shortly before the Maharaja too passed away in 1853. The adoption was witnessed by courtiers and the British political officer who was handed a letter from the Maharaja instructing that the child be treated as his legitimate heir and the kingdom’s affairs be entrusted to the care of his widow for her lifetime.

The British failed to honor the adoption. Instead, they used the Doctrine of Lapse cunningly employed by the British Governor-General Lord Dalhousie to annex Jhansi and other heir-less Indian kingdoms to British rule. In March 1854, Rani Lakshmibai was awarded an annual pension of Rs60000 and ordered to leave the palace and the fort. The order outraged the dowager queen who defiantly asserted “I will not surrender my Jhansi”.

Refusing to bow to fate’s cruel hand, she went to war with the enemy. Her valor inspired not only men but women to join her cause. Like Gandhi a half-century later, she helped women in her kingdom to break their shackles of domesticity and embrace the challenges of public life. In the battles that followed she fought valiantly, but suffered military reverses.

Facing an impending occupation of Jhansi by the British she escaped astride her horse with her adopted son tied to her back and regrouped her forces in Gwalior from where she made her last valiant venture to defend the fort of Gwalior. But the British forces were better equipped and stronger.

Fighting fiercely, dressed in the uniform of a cavalry leader, the soldier queen – wounded and unhorsed – died attaining the ‘Vir Gati’ – martyrdom that she had always sought. A quick cremation ensured that her last wish not to have her body captured by the enemy was honored. The year was 1858, and she was not yet 30.

As one of the leading figures of the 1857 “rebellion”, the Rani of Jhansi became a symbol of resistance to the British Raj for Indian nationalists. I remember at age 11, dressed in Rani’s style, a sword in hand, and enacting at a school function Subhadra Kumari Chauhan’s famous poem – “Khoob Ladi Mardani Voh to Jhansi Wali Rani thi” – a tribute to Rani’s valorous male-like martial skills. Books and films over the decades have captured and replenished her legend.

It is appropriate to turn to one of the oldest works on her – ‘Lachmi Bai, the Joan of Arc of India’ by Michael White, published in 1901. He wrote: A second Jeanne D’Arc, as valiant in battle, more subtle in council than the Maid of Orleans, moved by the same passionate love for her country, had cast in their teeth a wager of defiance, to stand until either they were driven from her state, or she had perished.

Neera Kuckreja Sohoni