By Sarika Sharma

A reluctant assistant to her mother, Ravinder Bhogal’s life story move around food. Her Nairobi home would smell of Indian spices and buzz with desi chatter. Her little aluminum stove was where she first made rotis singed and bitter, yet relished by her grandfather. The scent of guavas from her African home evoked déjà vu in London. She sought solace in clementines under the pale light of her fridge, found it in planning meals for the family. Amid this backdrop, was it natural for her to turn a chef? You could say yes, even if she veered off a bit earlier and started out being a journalist.

Bhogal is out with her new book, ‘Jikoni: Recipes from an Immigrant Kitchen’. Jikoni means kitchen in Kiswahili, the language of Kenya; it is also the name of her London restaurant. And this book is an ode to the many lands human beings traverse for sustenance, desire or exploration — she calls it an amalgamation of “proudly inauthentic recipes”. In here, kimchi serves as filling for parathas and smoked mackerel combines with potato dosas. Baked cornflour chevdho replaces the deep-fried delight from India; British game Venison becomes the stuffing of clove-smoked samosas; apple achar pairs with matthis and paneer with Spanish Padron peppers; coffee flavours rasgullas, which are in turn paired with mascarpone ice cream and espresso caramel. Apple jalebis are served with fennel ice cream and ubiquitous kheer turns vanilla kheer creme brulee.

For her, this fusion of cultures began early on. Her grandfather had migrated to Africa in the 1940s from rural Punjab and she remembers the household in Kenya adapting to the local spices and produce. She says they cooked Indian food through an African lens. “…techniques and recipes were traditional to India but adapted to local ingredients. It also meant adopting East African food or ingredients, but cooking with Indian spicing. This resulted in many great hybrid dishes such as kuku paka, a coastal chicken curry that combines African, Indian and Arabic traditions,” says Bhogal. Being a small Indian community in East Africa also meant food came from many regions in India. However, the Punjabi traditions, like sarson ka saag, kadhi pakoda and dal makhani, were maintained well.

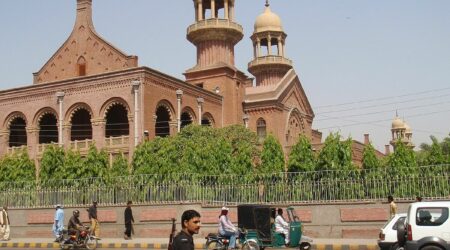

When she was seven, the family moved to London. The never-ending, cold grey days made her long for the warmth of Kenya, its red, wet earth… She remembers being unwell and longing for pink guavas. Homesick for a long time then, she now understands that immigrants always have to be ready to adapt. “I think you settle when you learn to reconcile your own culinary heritage with the new ideas your new home offers. This leads to some pretty exciting hybrid dishes,” says Bhogal, who has had stuff like okra fries with curry leaf mayonnaise and cucumber and gin lassi on the menu of the restaurant she opened in 2017. She calls it “No Borders Kitchen”, and we wonder how purists have reacted to her ‘inauthentic’ recipes. Bhogal says she hasn’t had any real negative feedback. “Once people understand that I am not running an Indian restaurant and know our philosophy, they are already expecting something different. I find the idea of authenticity restrictive,” she says, adding, “The question I always ask is not what makes this authentic, but rather what makes it most delicious. And if that means crossing a border, so be it.”

For her, food, people, place and identity rustle up a powerful relationship and that is exactly what she calls ‘immigrant cuisine’. The tastes and smells of this brazen new world are sophisticated, welcoming, fresh, exciting and bold. She says her recipes are inspired by the taste of home, and home could be anywhere — Kenya, where she first understood food and flavors; London, where her love for it all found shape; Punjab, where her parents came from but left more than 80 years ago, or the many aromas she discovered along life.

Finding liberation, in the kitchen

“As I watched my grandmother, mother, aunts and sisters join the cult of domesticity, I felt restless and inwardly rebelled at the drudgery of it all.” In the introduction to her new book, Jikoni, chef Ravinder Bhogal talks, in very clear terms, about how in patriarchal Indian families cooking has been assigned to women, with or without their consent. However, powerful female role models such as Madhur Jaffrey and Nigella Lawson gave her faith that cookery could be a career prospect, rather than just a feminine duty. “I also think the kitchen can become a very liberating space for women if they make the choice to be there or if like me, they choose to make a career out of it,” she says.

Source The Tribune, Chandigarh

In Ravinder Bhogal’s ‘Jikoni’ book, kimchi serves as filling for parathas and smoked mackerel combines with potato dosas. Venison becomes the stuffing of clove-smoked samosas; apple achar pairs with matthis and paneer with Spanish Padron peppers; coffee flavored rasgullas are paired with mascarpone ice cream and espresso caramel.

Born in East Africa and raised in the UK, Punjabi-origin chef Ravinder Bhogal’s immigration cuisine spans geography, ethnicity and history.